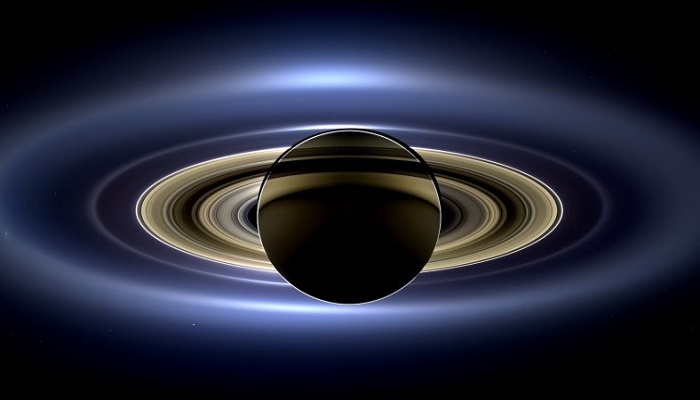

Cassini: Saturn probe turns towards its death plunge

The international Cassini spacecraft at Saturn has executed the course correction that will send it to destruction at the end of the week.

The probe flew within 120,000km of the giant moon Titan on Monday – an encounter that bent its trajectory just enough to put it on a collision path with the ringed planet.

Nothing can now stop the death plunge in Saturn’s atmosphere on Friday.

Cassini will be torn to pieces as it heads down towards the clouds.

Its components will melt and be dispersed through the planet’s gases.

Ever since it arrived at Saturn 13 years ago, the probe has used the gravity of Titan – the second biggest moon in the Solar System – to slingshot itself into different positions from which to study the planet and its stunning rings.

It has been a smart strategy because Cassini would otherwise have had to fire up its propulsion system and drain its fuel reserves every time it wanted to make a big change in direction.

As it is, those propellants are almost exhausted and Nasa is determined the spacecraft will not be permitted to just drift around Saturn uncontrolled; it must be disposed of properly and fully.

The agency called Monday’s last encounter with Titan the “kiss goodbye”.

“Cassini has been in a long-term relationship with Titan, with a new rendezvous nearly every month for more than a decade,” said Earl Maize, the Cassini project manager at Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

“This final encounter is something of a bittersweet goodbye, but as it has done throughout the mission, Titan’s gravity is once again sending Cassini where we need it to go.”

Closest approach to the moon’s surface occurred at 19:04 GMT (20:04 BST; 15:04 EDT; 12:04 PDT).

As the probe passed Titan, it gathered some images and other science data that will be streamed back to Earth on Tuesday.

The investigation of the 5,150km-wide moon has been one of the outstanding successes of the Cassini mission.

The spacecraft put a small robot called Huygens on its surface in 2005. It returned a remarkable image of rounded pebbles that had been smoothed by the action of flowing liquid methane. This hydrocarbon rains from Titan’s orange sky and runs into huge seas at northern latitudes.

Cassini also spied what are presumed to be volcanoes that spew an icy slush and vast dunes made from a plastic-like sand.

Cassini scientist Michelle Dougherty from Imperial College London, UK, says there will be an effort in the days up to Friday to try to squeeze out every last scientific observation.

“We’re now running on fumes,” she told BBC Radio 4’s Inside Science programme.

“The fact that we’ve got as far as we have, so close to the end of mission, is spectacular. We’re almost there and it’s going to be really sad watching it happen.”

Besides a last look at Titan, scientists want to get a few more pictures of the rings and the moon Enceladus, before then configuring the spacecraft for its dramatic scuttling.

The idea is to use only those instruments at the end that can sense Saturn’s near-space environment, such as its magnetic field, or can sample the composition of its gases.

In the final three hours or so before “impact” on Friday, all data acquired by the spacecraft will be relayed straight to Earth, bypassing the onboard solid state memory.

Contact with the probe after it has entered the atmosphere will be short, measured perhaps in a few tens of seconds.

The signal at Earth is expected to drop off around 11:55 GMT (12:55 BST; 07:55 EDT; 04:55 PDT). Engineers will be able to be more precise once they have looked at the position of the probe after Monday’s change in course.

“The Cassini mission has taught us so very much, and to me personally I find great comfort from the fact that Cassini will continue teaching us right up to the very last seconds,” said Curt Niebur, the Cassini programme scientist at Nasa Headquarters in Washington, DC.