War Crimes and Genocide in Yemen: Death, Destruction, Starvation

YemenExtra

Y.A

The Saudi-led coalition unleashed a barrage of air strikes on Yemen, slaughtering as many as 71 civilians (many of them children) within a period of 48 hours, reported the Qatar-based news network Al Jazeera on Christmas Eve. This massacre attained little attention and dissolved into history, forgotten. On the next day, December 26, the coalition targeted more sites, killing at least 68 men, women and children.

Those who are not annihilated by bombs risk dying from starvation. The Yemeni people are under blockade, enforced intentionally, with an aim to starve them into submission.

By definition a vicious war crime, it is not a newsworthy subject across the Western media sphere. Silence is particularly well kept at the U.S. news network MSNBC, found a study conducted by an investigative team of Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR). The leading liberal channel did not air a “single segment devoted specifically to Yemen in the second half of 2017.”

Unfortunately, there is a reason for this. Serving increasingly as a mere agent of power, the media implies silence when it protects and justifies the interests of our mighty “masters of mankind”, to borrow the words of Adam Smith. Therefore, the crimes committed by the forces we label as our ‘adversaries’, are there to be amplified and condemned. Atrocities committed by us and our allies are there to be overlooked, ignored. Consequently, this conventional practice divides victims into worthy and unworthy. If this phenomenon was to be rated, then Yemenis would perhaps represent the most unworthy victims.

The country falls into this model perfectly. To begin with, the bombs that destroy its infrastructure and kill its men, women and children are manufactured by the military-industrial corporations, which are headquartered in countries such as Great Britain and the United States. Furthermore, they are dropped on Yemen’s targets under intelligence support of the mentioned powers, by their regional allies Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Kuwait. These are the crimes of our empire and its client states, and therefore they would be forgiven and erased from the contemporary record.

However, after breaking conventional lies employed to justify the war, and after recovering the sources of what Vandana Shiva calls the “subjugated knowledge”, one will discover an inconceivable crime; perhaps the worst atrocity in decades being committed, precisely to propel the agenda of the most cynical forces controlling power.

It is past time to break the silence.

Our Ally in the Middle East

While the Saudi coalition has been bombing Yemen since 2015, not a word was uttered about its actions when American president Donald Trump visited Riyadh in May. It is forbidden to talk about human lives when a business that destroys them is booming. The Trump administration arrived in Riyadh to continue the legacy of its predecessors by signing a massive $109.7 billion arms contract with Washington’s corrupt and autocratic client state, promising high yields to the shareholders of America’s vast defense industry. Celebrating this contract, the business press published a piece with a headline stating: “Defense stocks at record highs on Trump-Saudi deal.”

It doesn’t matter that Saudi Arabia is a brutal theocratic and autocratic state, the single biggest sponsor of terrorism and a force waging an aggressive policy towards its neighbors in the Middle East.

In fact, Washington is well informed about it. An email released by WikiLeaks from the former Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, reveals it very instructively. While elaborating on the U.S’s fight against ISIS in Syria and Iraq, Clinton points out that “we need to use our diplomatic and more traditional intelligence assets to bring pressure on the governments of Qatar and Saudi Arabia, which are providing clandestine financial and logistic support to ISIL and other radical Sunni groups in the region.” A nearly identical conclusion was drawn in a cable dating back to 2009. It assesses that “donors in Saudi Arabia constitute the most significant source of funding to Sunni terrorist groups worldwide.” Though we leave this note for now, the subject of terrorism will appear again.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry walks with Adel Al-Jubeir, the newly named Saudi Foreign Minister, upon arriving at the Saudi Ministry of Interior in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on May 6, 2015, for a meeting and working dinner with Crown Prime Mohammed bin Nayef. (State Department photo)

Material support Saudi Arabia receives from Washington also signals a green light to its conduct in Yemen. It is worth stressing that the American empire plays an important role within the Saudi-led coalition. Adel al-Jubeir, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Saudi Arabia, spoke openly about the partnership with the co-anchor of CBS, Norah O’Donnell. Replying to her softly-pressed concern about the coalition’s use of indiscriminate bombing, he replied:

“We are very careful in picking targets, we have very precise weapons, we work with our allies, including the United States on these targets.”

Supporting its client state in his political goals, the United States helps the coalition to identify “targets” in Yemen. This is an important point. Since Washington is so deeply involved in the war, it too bears responsibility for war crimes. Investigating further, we will discover the extent to which the interests of these two powers bond in Yemen, both before and during the current war.

The myth about Iranian Proxies

The reason that Saudi Arabia, along with its coalition partners, is waging war in Yemen has been repeated ever since the conflict started. Riyadh is fighting Houthis, a former guerrilla movement from the country’s Shia-populated Northern Province of Sa’ada. The Saudi intervention came months after Houthi rebels advanced from their Northern stronghold into the Central and Southern Provinces of Yemen, captured major cities, including the capital Sana’a. Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, at that time Yemen’s serving President, fled the capital in 2014 to the Southern port city of Aden, where he stayed until fleeing to Saudi Arabia. The coalition started bombing Yemen immediately after his exile in March 2015.

Straightaway, the goal of the bombing was stated clearly: Riyadh sought to restore the government apparatus of President Hadi in Sana’a and crush the Houthi uprising. Justifying its actions, the Saudi coalition blamed Iran for supporting the rebel movement and thus destabilizing the entire region. Therefore, the coalition intervened in Yemen to stop the spread of Iranian influence on the Arabian Peninsula. Obediently, the Western news media amplified this message. A proxy war scenario was born. On 26 March 2015, the Guardian summarized events in Yemen in the following fashion: “The conflict, spreading outwards like a poison cloud from the key southern battleground around Aden, pits Saudi Arabia, the leading Sunni Muslim power, plus what remains of Yemen’s government against northern-based Houthi rebels, who are covertly backed by Shia Muslim Iran.” Thus “the primary Saudi aim is to pacify Yemen, but its wider objective is to send a powerful message to Iran: stop meddling in Arab affairs.”

This narrative is still relevant today. Under a premise that Houthis are no more than proxies of Iran, it is possible to draw a conclusion that Riyadh responds reciprocally to Iran’s actions. Of course, such a narrative is grossly oversimplified, though it is repeated routinely in the corporate papers, and thus it has become a conventional wisdom. Before breaking down this myth, it is worth stressing that even if the conflict is portrayed as a regional fight between the two rivals – Riyadh and Tehran – the United States has numerously demonstrated its unilateral position on the issue. Speaking at the Arab Islamic American Summit in Riyadh, President Trump made it clear that

“Iran funds, arms, and trains terrorists, militias, and other extremist groups that spread destruction” across Lebanon, Iraq and Yemen.

In this context, Iran’s destabilizing “extremist groups” in Yemen are the Houthis. Such a statement will not be a surprise for those who listened to the earlier remarks of the U.S. Secretary of Defense, James Mattis, who described Iran as “the single biggest state sponsor of terrorism in the world.” As we already know, this is a lie.

The nucleus of the argument that Iran is fighting a proxy war in Yemen stresses that Houthis receive their weapons from Tehran. Indeed, in order to see how much support Iran provides to Houthis, it is worth examining the U.S. diplomatic cables. Classified by the U.S. Ambassador to Yemen, Stephen Seche, a cable from 9 December 2009 (when the rebels operated in Sa’ada Province) examines:

Contrary to ROYG claims that Iran is arming the Houthis, most local political analysts report that the Houthis obtain their weapons from the Yemeni black market and even from the ROYG military itself. According to a British diplomat, there are numerous credible reports that ROYG military commanders were selling weapons to the Houthis in the run-up to the Sixth War. An ICG report on the Sa’ada conflict from May 2009 quoted NSB director Ali Mohammed al-Ansi saying, “Iranians are not arming the Houthis. The weapons they use are Yemeni. Most actually come from fighters who fought against the socialists during the 1994 war and then sold them.” Mohammed Azzan, presidential advisor for Sa’ada affairs, told PolOff on August 16 that the Houthis easily obtain weapons inside Yemen, either from battlefield captures or by buying them from corrupt military commanders and soldiers. Azzan said that the military “covers up its failure” by saying the weapons come from Iran. According to Jamal Abdullah al-Shami of the Democracy School, there is little external oversight of the military’s large and increasing budget, so it is easy for members of the military to illegally sell weapons.

The cable also points out that Houthis are a “decentralized guerrilla army”, retaining support from Sa’ada residents “because of ROYG [Republic of Yemen Government] injustices, abuses by local sheikhs, and the brutality of the war.” Although the Houthi military wing can be classified as religiously motivated, its leader, Abdulmalik al-Houthi, is described as a “political-military leader rather than a religious one.”

Grievances of Sa’ada residents towards Sana’a are legitimate. Since the Houthi uprising started in 2004, the Yemeni government under President Ali Abdullah Saleh has been waging a violent campaign against the group. Back then, Saudi Arabia also sought to “pacify Yemen”, and supported Sana’a in its campaign by bombing the Northern Province. From what U.S. diplomatic cables reveal, Riyadh’s previous conduct in Yemen against Houthis is strikingly similar to the strategy applied since 2015.

A cable dating from 30 December 2009 explains that “the Saudi military has employed a massively disproportionate force in its effort to repel and clear the lightly armed Houthi guerillas from the border area.” Of course, the “disproportionate force” cannot be employed without assistance from Washington.

During the campaign, the Saudi military turned to the U.S. for emergency provision of munitions, imagery and intelligence to assist them to operate with greater precision. The U.S. military responded with alacrity to the extent possible, primarily by flying in stocks of ammunition for small weapons and artillery.

This conflict received practically no media coverage in the West, though it affected at least 150,000 civilians. The precise number of people killed in six wars between 2004 and 2010 is unknown.

As it was pointed out earlier, there is no direct arms link between Iran and the Houthis. Consequently, it did not matter to the Saudis, and therefore their intention to crush the rebels can be attributed to a different cause.

The Saudi Colony

What should be analyzed then is the sudden rise of the Houthi movement in 2014. Did something change between December 2009 and September 2014, when the rebels captured Sana’a? Is Iran the sponsor of their victories?

The answer perhaps lies in the political shifts the country experienced during the Arab Spring, and in the relationship of its establishment elite with the regional powers. One of the central figures of our assessment is, therefore, Ali Abdullah Saleh, the long-serving President who united the territories of North and South into one country that is Yemen in the 1990s. Holding power for over 3 decades, he was forced to resign amidst protests in 2011. Two years after handing the post to his deputy, Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi, Saleh formed an alliance with the Houthis. Hence the start of the war; the armed forces loyal to the former President aided the rebels to fight against the ground militants of the Saudi-led coalition and exiled President Hadi.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and Yemeni President Abdo Rabbo Mansour Hadi address reporters before their bilateral meeting at the U.S. Department of State in Washington, D.C., on July 29, 2013. (State Department photo)

One would be correct, however, to label the alliance fragile. Looking into to the past record of Saleh, one perhaps should read a classified cable from 16 November 2009. While assessing the Saudi military involvement in Northern Yemen, it presses that “President Saleh has long been encouraging Saudi Arabia to join the fight” against Houthis. Therefore, “In the short-term at least, it seems like President Saleh has gained the most from the Saudis’ entry into the conflict. His glee when the Saudis launched their airstrikes indicates he finally received what he has been pushing for— political, financial, and direct military support for the war from Yemen’s powerful neighbor and principal benefactor.” It is vital to keep in mind that the two sides – Saleh and Houthis –would in future be united against the Saudi coalition.

A secret cable from June 18, 2008, nonetheless indicates that in the overall process, Saleh and the Yemeni political establishment could perhaps be the “second class” beneficiaries. This particular cable is long and extremely informative. In it, Sana’a’s relationship with Riyadh is described as following:

Yemenis perceive the relationship as heavily balanced in favor of Saudi Arabia, which remains involved in Yemen, to the extent necessary, to counter the potential threat of Yemen’s unemployed masses, poor security, unrest, crime and the intentions of foreign countries (Libya and Iran) that might create a threat on Saudi Arabia’s southern border.

Striking deals with the country’s corrupt elite and providing “substantial development assistance”, Riyadh is indeed countering “the potential threat of Yemen’s unemployed masses.” In this context, the Houthis perhaps represent the biggest threat, as they attract support from people who are tired “of ROYG injustices” and “abuses by local sheikhs.”

Assessing the tribal factor that plays a significant role both in shaping the internal politics and external relationship between Yemen and its Northern neighbor, the cable outlines: “Yemen’s proximity to Saudi Arabia and their history means that many tribes in Yemen share ancestry with Saudi Arabia.” At the same time, it points out:

Yemenis are aware that other Arab nationalities, including Saudis, see them as backward uncivilized people. In ref B, Yemeni Colonel Handhal, commander of al-Badieh military airfield near the Saudi border, said that Saudis treat Yemenis as second class citizens. This second class designation may extend to the official level as well.

Pipeline Project

It is therefore logical that Riyadh is pursuing to use Yemen for its self-benefiting projects.

A British diplomat based in Yemen told PolOff that Saudi Arabia had an interest to build a pipeline, wholly owned, operated and protected by Saudi Arabia, through Hadramaut to a port on the Gulf of Aden, thereby bypassing the Arabian Gulf/Persian Gulf and the straits of Hormuz. Saleh has always opposed this. The diplomat contended that Saudi Arabia, through supporting Yemeni military leadership, paying for the loyalty of shaykhs and other means, was positioning itself to ensure it would, for the right price, obtain the rights for this pipeline from Saleh’s successor.

The construction of a pipeline which will connect the Eastern oil fields of Saudi Arabia with the Gulf of Aden is a strategic goal. If implemented, the Hadramaut project will have a geopolitical significance. “Bypassing the Arabian Gulf/Persian Gulf and the straits of Hormuz”, the pipeline could potentially reshape the map of oil shipment routes in the Middle East. The problem with an established order was indicated by Anthony H. Cordesman, the Chair in Strategy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a major foreign policy think tank based in Washington D.C. His article published on 26 March 2015, a day after Riyadh and its allies began bombing Yemen, indicates the current significance of the Strait of Hormuz as “the world’s most important oil chokepoint because of its daily oil flow of 17 million barrels per day in 2013. Flows through the Strait of Hormuz in 2013 were about 30% of all seaborne-traded oil.” Therefore, the problem lies in the lack of “functioning pipelines that provide alternative export routes.” While the issue of dependence of global oil exports on the Strait of Hormuz was not conveyed explicitly, it can logically be nothing other than Iran. A close proximity of the world’s most important oil route to the adversary of the American empire seems to cause a headache to Washington strategists. Thus the construction of the Saudi pipeline through Yemen represents an explicit step in the right direction.

As it maintains a cold war relationship with Tehran, the Saudi Kingdom foresees its dependence on the Strait of Hormuz as a strategic weakness, too. Redirecting the oil exports to the Gulf of Aden and hence to the Red Sea would be a win/win venture for both Riyadh and Washington; the Red Sea route is a vital oil shipping lane to Western countries, protected by the empire’s client states such as Djibouti, a country that is also a military base of East Africa, hosting as many as 5000 troops from Europe and the United States.

Returning to the cable, it was vividly stated there that President Saleh “has always been opposed” to the Hadramaut pipeline. His opposition was, of course, unacceptable to Riyadh, the same as any opposition that comes from the “backward” and “uncivilized” Yemen. The bet was that “Saleh’s successor” and his establishment would implement this project for “the right price.” Thus, a campaign to remove Saleh from power was enabled. Though the Yemeni leader would step down in 2011, WikiLeaks reveals that the plan of action for his removal was crafted as far back as 2009. A classified cable from 31 August 2009 portrays an influential figure within the right-wing Salafist (an ultra-conservative branch of Sunni Islam) Al-Islah party, Hamid al-Ahmar, threatening to organize mass demonstrations to oust Saleh.

Hamid al-Ahmar, Islah Party leader, prominent businessman, Member of Parliament, and de facto head of the Hashid tribal confederation, told EconOff on August 27 that he had given President Saleh until the end of 2009 to “guarantee” the fairness of the 2011 elections, form a unity government with the Southern Movement, and remove his relatives from military leadership positions. Absent this fundamental shift in Saleh’s governance of the country, Ahmar will begin organizing anti-regime demonstrations in “every single governorate,” modeled after the 1998 protests that helped topple Indonesian President Suharto.

“We cannot copy the Indonesians exactly, but the idea is controlled chaos.”

Mr. Ahmar nonetheless debunks his ultimatum and clarifies:

“There’s really no way to verify that Saleh is serious about free and fair elections, but I won’t wait until the 2011 elections to move forward.”

Implementing the “controlled chaos” to oust the long-serving President, whose family commands the country’s military apparatus, is rather a difficult task requiring external assistance.

Removing Saleh from power in a scenario that does not involve throwing the country into complete chaos will be impossible without the support of the (currently skeptical) Saudi leadership and elements of the Yemeni military, particularly MG Ali Muhsin, according to Ahmar.

“The Saudis will take a calculated risk if they can be convinced that we can make Saleh leave the scene peacefully.”

Saleh’s successor, Ahmar noted, should be close to Riyadh and come from the South.

Denying any personal ambition to lead the country, Ahmar said that Yemen needs a president from one of the southern governorates and that the Saudis would eventually come around to the idea.

“If the Saudis were going to put anyone in power instead of Saleh, it would be me — everyone knows I am close to them — but I told them the next president must be a southerner, for the sake of unity.”

United Decentralized Yemen

Large demonstrations against Saleh started on 27 January 2011, amidst the winds of the Arab Spring challenging dictators in Egypt and Tunisia. Marginalized by the country’s “sheikhs” and political establishment, Yemenis too wanted change to the status quo. Their demands, however, were exploited from the beginning. It is worth remembering that the uprising was to be “controlled.”

Organizing protests was the opposition comprised of different factions – all challenging the General People’s Congress, a party of President Saleh. Their symbiosis with the marchers, however, is quite interesting to look at. An article about the student protests in Sana’a, published on 13 February 2011 by the New York Times, points out the difference between the spontaneous popular demonstrations and organized marches.

Unlike the earlier protests in Yemen, which were highly organized and marked by color-coordinated clothing and signs, the spontaneity of the younger demonstrators appeared to have more in common with popular uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt, where opposition groups watched from the sidelines as leaderless revolts grew into revolutions.

Hamid al-Ahmar is featured in the article. He articulates the conflict of interest between the protesters and their opposition organizers. A popular uprising against the establishment was indeed not on the agenda.

Sheik Hamid al-Ahmar, an opposition leader, said in an interview on Sunday that political leaders had tried to prevent the younger demonstrators from taking to the streets to demand immediate changes to the autocratic rule of Mr. Saleh. But, he said, “It’s not that they aren’t cooperating with the new protests,” only that opposition leaders would like to move more slowly.

Predictably, the government security forces responded viciously to the protests. Hundreds of people died in clashes. As planned, the Gulf countries got involved in the crisis. They crafted an agreement to ensure Saleh’s ‘peaceful’ resignation, which the Yemeni leader signed on November 23. The New York Times reported on the deal:

According to a Gulf-brokered agreement, which Mr. Saleh signed on Nov. 23, he and his family must give up their powers in exchange for immunity and allow for a peaceful, democratic transition from his 33-year rule. The military, which was divided during the protests and brought the country to the brink of civil war last summer, must also be restructured and integrated.

Another article, published on the same day as Saleh resigned, amplified the concern of protesters that the agreement “would preserve the status quo by keeping the country’s elite” in power.

Their concerns were nonetheless irrelevant. All parties representing power worked “to counter the potential threat of Yemen’s unemployed” and “uncivilized” masses. As diplomatic cables reveal, American empire supported Saleh as its close ally prior to the events in 2011. Simultaneously, it sought to use “Saudi Arabia to address development in Yemen.” Therefore, Washington supported the deal which ousted Saleh and attained similar alliance with his successor. Coming from the South and thus ensuring Yemen’s unity, while also playing to the interest of Riyadh, Mr. Hadi consolidated the objectives expressed in 2009 by Mr. Ahmar.

Moving forward, President Hadi enabled procedures to establish a suitable environment for the implementation of Saudi goals. On March 18, 2013, the National Dialogue Conference was kick-started in Sana’a— backed by the United Nations and hosted at the luxurious Movenpick Hotel. To the Western audience, the conference was portrayed as a reconciliation effort, aimed at resolving the existing differences between the Yemeni factions (political parties and secessionist movements). The real agenda was hidden behind closed doors. Observing the conference, an article published on the news blog of the Atlantic Council points out that a weakness of the National Dialogue is a lack of “communication with the Yemeni public.” The hotel where the conference was hosted has been “reportedly packed with foreign governance experts and consultants who are being handsomely compensated, but little is known regarding the affiliation of these experts, what technical assistance they are offering Yemenis, or whether their role is beneficial and effective.”

In a revealing analysis published in 2015 on her personal blog, which she later deleted, the Senior Advisor for Security/Rule of Law/Human Rights at the Netherlands Embassy in Yemen, Joke Buringa, summarizes the processes in the country as follows.

When the situation really became untenable the Gulf States, under the watchful eyes of the US and the EU, convinced Saleh to step down in exchange for immunity. His Vice-President Hadi would take over the presidency until the planned presidential elections. De facto, the existing system was kept intact. The subsequent National Dialogue led to the decision to form a federal state with six countries. The governorates of Hadramaut, Shabwa and al Mahra were to come together in a new state called Hadramaut. When asked last year, the current Yemeni minister of Information Mrs. Nadia Sakkaf (residing in Riyadh) could not explain how that decision was reached: one day it had simply been made. The new state of Hadramaut counts 4 of the 26 million inhabitants of Yemen, 50% of the land area, 80% of the oil exports and – contrary to large other parts of Yemen – a sufficient water supply. In addition, a gold reserve worth 4 billion US dollars has recently been discovered.

Not only will this plan turn Yemen into a decentralized colony of Riyadh, but it will also spearhead implementation of the Hadramaut pipeline, which will be accepted “for the right price” by tribal leaders and corrupt sheikhs. Bypassing the populated and resources-scarce Eastern Provinces through the autonomous and sparsely populated Hadramaut would also provide enough means for the Saudis “to counter the potential threat” of the Yemeni people. In accordance with the plan, Yemen will nonetheless remain a united country, at least on the map. Separating the Northern Provinces from the South was clearly not on the agenda; perhaps because controlling two sovereign countries would be more difficult.

In the article, Buringa also observes “the governorate of Hadramaut is one of the few areas where the Saudi-led coalition did not conduct any airstrikes.” Thus “the port and the international airport of Al Mukalla are in optimal shape and under the control of Al Qa’eda. Moreover, Saudi Arabia has been delivering arms to Al Qa’eda, who is expanding its sphere of influence.” Controlling vast swaths of a territory of what has proven to be a vital Province for the Saudi interest, Al Qa’eda was tolerated; its grip on Al Mukalla, the fifth largest city in Yemen, was broken in 2016, retaken by the coalition-backed militias. The city was recaptured almost immediately, just a day after the offensive was launched.

While details about the pipeline project have remained unspoken in the media sphere, the fragmentation of Yemen into semi-autonomous regions has gained some attention. Shortly after the end of negotiations, the British Broadcasting Corporation reported on 10 February 2014 that Yemen will “become a federation of six regions” – “two in the south – Aden and Hadramaut – and four in the north – Saba, Janad, Azal and Tahama.” The new decentralized government structure will be “enshrined in a new constitution.” The existing differences between the North and South was a conventional explanation for the decision to implement a decentralized system of governance.

An outcome of the conference was praised internationally. The State Department spokesperson, Marie Harf, welcomed the National Dialogue conference as “evidence of the will of the Yemeni people to work together constructively for the future of their country.” Canadian Minister of Foreign Affair, John Baird, congratulated “the people of Yemen” for having “spoken for a more open society that respects freedom, democracy, human rights and the rule of law.” Voices from within Yemen did not necessarily share the optimism. The Houthis rejected an outcome, stressing that “it divides Yemen into poor and wealthy” regions.

The political reality outside of the Movenpick Hotel was a power vacuum. It is safe to say that Hadi’s transitional government was highly unpopular among the people, representing a status quo they fought to topple. The security apparatus was also divided, with a large faction of the military remaining loyal to the former President. Consequently, not Iran but a failure of the fractured army to foster a coordinated effort against the Houthis, provided them the necessary power vacuum to expand. It seems that the subsequent alliance between Saleh and Houthis was merely political – an attempt from his side to retake control of Sana’a. This political shift nonetheless had a significant impact on the planned implementation of a framework from the National Dialogue. Combined together, the two factions have formed a force neutral to sectarian differences and strong enough to challenge Hadi’s government and its international backers.

This is unforgivable.

Starving the Rebellion

Nothing can morally justify the coalition intervention in Yemen – especially the naval blockade it imposed on the country of 28 million people, the poorest in the Arab world. Examining its conduct closely brings a shocking revelation. It is pure barbarism, to say the least.

The blockade was enforced just days after the coalition began its air campaign. Food security for millions of Yemenis was already dire prior to the conflict. With less than 3 percent of the land being used for agriculture, Yemen struggled to meet the demands of its growing population. Domestic cereal production, for instance, covers less than 20 percent of the total internal demand, while at a minimum, 90 percent of all wheat is imported from abroad(this was not the case just a few decades ago). Severely restricting the importation of essential goods –machinery equipment, medicines and food – the blockade has created an environment for a humanitarian catastrophe. One of Yemen’s vital ports located in the city of Al Hudaydah –a Houthi controlled port supplying imports to country’s largest cities, including the capital Sana’a – was severely impacted, often staying idle for weeks as ships are stuck in the waters, prevented by the coalition from docking. Indeed, a goal of the blockade is vicious though explicit: use starvation as a weapon against the Houthis and Yemeni civilians in disregard of international law.

Returning from his visit to the country in 2015, Peter Maurer, the head of the International Red Cross Committee, observes “Yemen after five months [of war] … looks like Syria after five years.” A report released on 10 June 2015 overlooking the food security situation confirms Maurer’s assessment. Using the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification scale that divides the population into five categories – generally food secure (phase 1) to famine (phase 5) – it estimated 6,071,831 people were experiencing humanitarian emergency (phase 4), just a step away from famine. The United Nations warned of a potential famine, and the media conglomerates have periodically amplified its message.

It is a fact that the situation has deteriorated dramatically since then. In the following summer of 2016, the population under humanitarian emergency surpassed 7 million. Most recent data on the situation was reiterated by the humanitarian coordinator for Yemen, Jamie McGoldrick. Stressing that

“the continuing blockade of ports is limiting supplies of fuel, food and medicines; dramatically increasing the number of vulnerable people who need help,” McGoldrick warned “8.4 million Yemenis” are “a step away from famine.”

Indeed, the coalition has been implementing its starvation tactic quite methodically. Air campaigns have targeted infrastructure that is essential for maintenance of life, for example; bridges, airports, food warehouses and agricultural production. In fact, the precision with which the coalition planes strike these targets is shocking. Martha Mundy, the emeritus professor at the London School of Economics and author of a report about the war on Yemen and its agricultural sector, commented for this piece:

“the evidence from the total pattern of bombing and the blockading of ports is that disruption of production, processing distribution of food forms a central part of the Coalition strategy.”

The report itself confirms this instructively. Using conservative data from the ministry of agriculture and irrigation in Sana’a, it concludes between March 2015 and August 2016 the coalition targeted 257 farms/animal farms, 30 sites related to water infrastructure and dozens of food storage facilities and markets. The Sa’ada Province suffered particular damage; small rural areas were bombed and agricultural life systematically disrupted. Vividly, the bombing was intending to inflict starvation, a vicious war crime.

Agricultural production hence declined amidst the fact that Yemen has enjoyed satisfactory rainfall. The total cereal harvest in 2017 was predicted to be half of the five-year average (that includes time before the war). Simultaneously, the distribution of imported food into the rebel-controlled territories is difficult. Dr. Mundy writes the blockade is “encouraging traders to move food either through southern ports or across land borders,” thus “forcing prices up massively” in the markets. “There is good evidence,” she points, “of processed food flowing in from Saudi Arabia overland, the issues being of course the destruction of food processing plants in Yemen by air strikes and the price that the imported goods then cost.”

In the Houthi-controlled coastal areas, the coalition enforces its blockade by restricting boats from sailing into the sea. Small fishing vessels have repeatedly come under attack, with crew members – sometimes the only family breadwinners – killed or severely wounded. Thus starvation prevails in the communities.

Evidently, civilians are bombed indiscriminately; in fact, 3158 coalition air strikes hit civilian targets between March 2015 and August 2016, concluded the Guardian after reviewing records from an independent data collection project known as The Yemen Data Project. At that time, the project recorded 8617 strikes across Yemen. The number has since increased dramatically, topping 15489 by mid-December 2017. How many of them hit agricultural production, infrastructure and civilian areas?

Exacerbating the impact of the mentioned “forms of aggression,” stresses Dr. Mundy, is the “economic war that takes the form of moving the central bank to Aden [controlled by pro-coalition forces] and then failing to pay government employees throughout all the areas under Houthi/GCP [General People’s Congress] control.”

Apart from contributing to rising prices, the economic war struck a devastating blow to the assets of public use. 72 percent of Yemeni teachers, for instances, have not received salaries for months, leaving over 4.3 million students without education, concludes the latest report on humanitarian needs

Making an empirical assessment on the human toll of the coalition war is virtually impossible. The official death toll only accounts for fatalities from the combat zones and air strikes. By this measurement, around 10,000 people have died since 2015. This estimate was first revealed to the media by the UN humanitarian coordinator to Yemen in August 2016 and remained practically static ever since. There is no doubt that thousands more have died from the blockade.

It has already caused the worst cholera outbreak in recorded history, with over one million people infected and 2237 deaths; of course, that is if one believes the official fatalities record. Hunger is also taking countless lives. A UNICEF report dating from 12 December 2016 voiced alarm about increasing child mortality with its estimate of one child dying every ten minutes from acute malnutrition and diseases (no longer treatable under the blockade). Considering that conditions on the ground have not improved, it is plausible that over 55,000 more Yemeni children have died between 12 December 2016 and 1 January 2018. Another plausible estimate can be made with the data from the mentioned above IPC reports. By definition, between one and two deaths are occurring within the population of 10,000 per day under phase 4 humanitarian emergency. Placing into the equation 8.4 million people who live in conditions of humanitarian emergency, and using the nominal mortality rate of its definition, would mean as many as 840 deaths are occurring daily across the country. Amidst the repeated warnings, famine has not yet been officially acknowledged, and perhaps it will not be until the situation becomes too critical to ignore.

“It is not clear who would declare the famine,” Dr. Mundy says. “The statements of the UN Humanitarian Affairs Officer in Yemen are as close to authoritative for the international agencies as one can get. For obvious reasons the Houthis have little to gain by declaring that there is a famine.”

An instructive warning was once echoed in the article on Time:

“The last time famine was formally declared, in Somalia in 2011, most of the 260,000 victims had already died.”

It is, unfortunately, valid to say that an overall death toll from the Saudi-led coalition war and blockade now ranges within borders of hundreds of thousands.

Making Excuses for the Genocide

There was a remarkable spectacle in Washington D.C recently. Inside a warehouse at the Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling military installation was Nikki Haley, the United State ambassador to the United Nations, speaking before a group of reporters. On the background were the remnants of what we should believe is a missile – the “Iranian missile”, as she describes. The premise for Haley’s presentation was Yemen, where Houthis fired a missile directed towards King Khalid’s International Airport in Riyadh on November 4. Condemning rebels for targeting a “civilian airport”, the ambassador warned about Iran’s “destabilizing behavior” in the region. In Colin Powell’s fashion, Haley descended that “we must speak with one voice in exposing the regime for what it is: a threat to the peace and security of the entire world.”

Indeed, there is not a lot, really, that can justify the rebel launch of a missile towards Riyadh, although the motive was clearly retaliatory. While condemned, the attack killed no one; the missile was intercepted. By contrast, the Saudi-led coalition was not condemned when it bombed civilian airports in Yemen, including the complex in Sana’a. In her presentation, Haley mentioned nothing about the coalition air crimes, about its deliberate policy of starving Yemenis to death. This is not something the ‘world community” should be concerned about. Highly publicized, the presentation has, in fact, once again validated the coalition war and justified the naval blockade. Perhaps one would not be wrong for calling the speech ‘a formal excuse for genocide’.

Again, it is worth remembering that there is no explicit arms link between Iran and the Houthis. From the beginning, however, the coalition employed Iran’s material support for rebels to justify the naval blockade. It has become a conventional fact that Iranian weapons, transported on boats via what is one of the world’s most patrolled sea routes, is what keeps the rebel resistance going. The theory is ludicrous, to say the least.

It is therefore not a surprise that one aspect of the war in Yemen has gained less media attention than anything else – concrete evidence of the coalition’s success at stopping Iranian weapons from flowing into the rebel arsenals. Perhaps there are two reasons for that. First, there is nothing really to present before journalists. Second, the United States and some of its NATO allies are too heavily involved in the blockade enforcement. Reporting for the Consortium news on 31 October 2016, an investigative journalist, Gareth Porter, powers the two claims with evidence.

Secretary of State John Kerry introduced the new variant of the Obama administration’s familiar theme about Iran’s “nefarious activities” in the region two weeks after Saudi Arabia began its bombing in Yemen on March 26, 2015. Kerry told the PBS NewsHour, “There are obviously supplies that have been coming from Iran,” citing “a number of flights every single week that have been flying in.” Kerry vowed that the United States was “not going to stand by while the region is destabilized.”

Later, the administration began accusing Iran of using fishing boats to smuggle arms to the Houthis. The campaign unfolded in a series of four interceptions of small fishing boats or dhows in or near the Arabian Sea from September 2015 through March 2016. The four interceptions had two things in common: the boats did have illicit weapons alright, but the crews always said the ship was bound for Somalia – not Yemen and the Houthis.

But instead of acknowledging the obvious fact that the weapons were not related to the Iran-Houthi relationship, a U.S. military spokesman put out a statement in all four cases citing a U.S. “assessment” that the ultimate destination of the arms was Houthi-controlled territory in Yemen.

These boats were intercepted by the navy of countries participating in the Combined Maritime Forces, a 32-nation coalition patrolling waters near the East coast of Africa and in the Gulf of Aden. Protecting a strategic trading route, the coalition is commanded from the U.S. navy base in Bahrain.

Pressure on Riyadh and its allies to lift the blockade remains pitiful. So far, there was perhaps only one instance when this crime against humanity had attained sizable publicity: it happened after the coalition tightened its siege to the point where even basic humanitarian supplies were no longer allowed to enter Yemen. A total blockade on air and sea was announced after the rebels fired a missile towards Riyadh’s airport, the event Nikki Haley exploited in her December theater of the absurd.

The twenty-day siege was later eased on November 26, 2017, amidst the mounting international pressure. However, with the first humanitarian cargo arriving in the rebel-held port of Al Hudaydah, the plight of Yemenis was once again forgotten. It did not matter that the siege remains tight, unjustified, supported by the world’s strongest power and violates international law.

“The situation in Yemen – today, right now, to the population of the country – looks like the apocalypse,” spoke to journalists the head of the UN office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Mark Lowcock. “Unless the situation changes, we’re going to have the world’s worst humanitarian disaster for 50 years.” Silence from the Western media conglomerates makes clear Lowcock’s statement was not newsworthy enough.

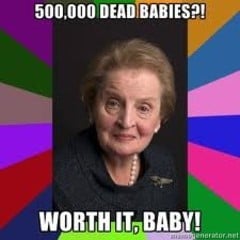

The reluctance of the American empire to cease its involvement and press on its Gulf allies to stop the unsought in Yemen is hardly surprising. Back in the 1990s, the U.S. and Britain were backing and justifying a similar medieval siege of Iraq. Killing as many as 500,000 Iraqi children was “worth it”, declared the Secretary of State for President Clinton, Madeleine Albright.

The Pragmatist is Gone

While the Gulf countries have advocated for Saleh’s resignation in 2011 in favor of President Hadi, they still regarded him and the General People’s Congress as the mainstream political forces, capable of maintaining a status quo that serves the interests of both parties: the Yemeni elite and Riyadh. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a foreign policy think tank based in Washington D.C, therefore observes that Saleh’s alliance with the rebels was an attempt to “use the Houthis” to “take revenge against his allies who defected from him in 2011.” Advancing from their Northern stronghold “Houthis saw in that an opportunity to grab power. Both, however, have been fierce enemies and fought six wars against each other between 2004 and 2010.”

As it was mentioned earlier, an alliance between the two was too fragile to stand. It collapsed by the end of November 2017, prompting a week of fighting in Sana’a between the loyalists of Saleh and Houthi rebels. Attempting to flee the capital on December 4, Saleh was caught and ambushed. Filming his corpse after execution, the fighters chanted “praise God, Sayyidi Hussein is avenged,” referring to Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi, a leader of the rebel movement sentenced to death under the orders of President in 2004. Saleh’s death has gained wide publicity across the media spectrum. There seems to be no hope left; peace between the coalition and Houthis is now unthinkable, we are told.

The Washington foreign policy think tanks agree. “With the passing of Saleh, the ultimate pragmatist with longstanding political and diplomatic ties both locally and internationally, an opportunity has passed with him,” assesses the Atlantic Council. If Saleh was alive, the only way to solve the crisis was to follow the United Nations Security Council “resolution 2216, which called on Saleh to change his destabilizing action, facilitate disarmament of the Houthis, and return to the National Dialogue Conference’s outcomes.” Hence an outcome where the Houthis are not represented and where Yemen was to be fragmented into six autonomous regions, controlled by and serving for the ventures of Gulf powers, including the construction of the Hadhramaut oil pipeline. A vivid exclusion of the rebel movement is justified: “the Houthis, an irrational movement lacking in political experience, make for a highly emotional and unreliable party at the negotiating table.” Perhaps the same is applicable to the Yemeni people, the “backward” and “uncivilized”, posing a “threat” to the regional powers and their Western backers.

Establishing whether the Houthis are “an irrational movement” in the Yemeni theater, one needs to compare them with the forces backed by the coalition and therefore representing the officially recognized government. As Neil Partrickwrites for the Carnegie think tank, the coalition has embraced “often rival Yemeni fighters as long as they are willing to fight Houthi or Saleh forces.” They are tribal militias and elements from political factions, including the Salafist Al-Islah party. Enhancing the alliance of “rival Yemeni fighters” are thousands of paid mercenaries, recruited from as far as the South American Colombia and as close as the African Sudan. Their ground activities are supervised by a limited number of soldiers from the Gulf countries, more precisely the United Arab Emirates. The U.S special operations forces are also on the ground, assisting their Emirate partners in missions.

Divisions nonetheless exist not merely between the armed militias who fight Houthis; there is competition for control and thus instances of tension between the main Arab actors involved in Yemen – Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Writing for the Carnegie think tank, Dr. Partrick puts the relationship between the two as following.

At times these differences have created competition for influence and even conflict. In February [2017], the Emiratis and their Yemeni allies fought Saudi-backed Yemeni fighters loyal to the nominal president Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi for control of the Aden airport, a struggle that prevented an Emirati plan to move north to Taiz. The risk of such confrontations remains, although because the UAE eventually secured control over the airport, it will likely focus on consolidating its existing southern power bases. Lacking ground forces anywhere in Yemen, the Saudis worry that the UAE could be carving out strategic footholds for itself, undermining Saudi influence in the kingdom’s traditional backyard.

Existing cracks within the anti-Houthi alliance perhaps reveal why the forces have made such a marginal progress against the group since 2015. In fact, the failure is quite dramatic, considering an unprecedented campaign the coalition enabled to force the Houthi-controlled territories into submission. One can only wonder what will happen to these factions if the prime enemy in the war is defeated. One would also be right to conclude that the officially recognized Aden-based government of exiled President Hadi maintains little to no authority over the country. The real power rests in the hands of the militias and their commanders.

With Saleh now dead, there is an expectation that his military and party loyalists will unite with the Saudi coalition to defeat the rebels. His son, Ahmed Ali Abdullah Saleh, a former head of the elite Republican Guard, has promised revenge:

“I will lead the battle until the last Houthi is thrown out of Yemen … the blood of my father will be hell ringing in the ears of Iran.”

It is impossible to establish whether his message had any ramifications on the ground. So far, little has changed to the status quo.

Receiving diplomatic protection and military support from Western powers, the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman is spearheading a purge of his royal princes at home and wages an increasingly aggressive foreign policy in the Middle East. It seems that he is prepared to go to great lengths to crush the rebels in Yemen, or at least to push them out of its major cities.

An opportunity for a more democratic Yemen was stolen from its people during the tumultuous months of the Arab Spring. The war and its culmination is what will determine the future of this ancient land. Managing to maintain resistance for almost three years against the superior military might of the Saudi-led coalition, Houthis remain perhaps the only established forces fighting for the country’s sovereignty. An alternative to their fight is the submission of Yemen to colonial powers.

Reading to this point, one would have to try hard in order to miss the sheer cynicism behind the war in the Arab world’s most marginalized and underdeveloped country. Conducted with weapons of the military-industrial corporations and made legitimate by the media apparatuses spinning deceptions as conventional facts, the perpetual policy of the world’s strongest powers towards Yemen has been a war; essentially, a war against its people, a strategy to counter their common interests, or a “threat”, as it is described. Internally, that means supporting the status quo of power being handled by a “pragmatist” and experienced elite, which understands the agendas of the mighty powers with its “longstanding political and diplomatic ties.”

Thus the lives of civilians are irrelevant – in Orwell’s lexicon, they are ‘unpeople’. It will be “worth it” if thousands of them perish in air strikes or die from hunger, so long as elitist goals are implemented, and the feasible status quo is maintained.

Nothing can justify this aggressive, this cynical war against defenseless people.

On 29 December 2017, Reuters published a rather exceptional report on the humanitarian impact of this continuing aggression. The author – SelamGebrekidan – writes about a new epidemic threatening thousands of people. On top of the ongoing cholera emergency, diphtheria is now spreading like wildfire. Reporting from a hospital in the coalition-controlled city of Aden, Selam conveys a story of an invisible crisis taking the lives of Yemen’s youngest and most vulnerable. Once with a chance of life on this Earth, they live no more.

Nahla Arishi, chief pediatrician at the al-Sadaqa hospital in this Yemeni port city, had not seen diphtheria in her 20-year career. Then, late last month, a three-year-old girl with high fever was rushed to Arishi’s ward. Her neck was swollen, and she gasped for air through a lump of tissue in her throat. Eight days later, she died.

Soon after, a 10-month-old boy with similar symptoms died less than 24 hours after arriving at the hospital.

Two five-year-old cousins were admitted; only one survived.

A 45-day-old boy, his neck swollen and bruised, lasted a few hours. His last breath was through an oxygen mask.

Thousands of miles to the West from Yemen is the government of the world’s mightiest empire, controlled by the interests of corporations and their shareholders on Wall Street. Indeed, the stock market has broken records in recent times, with defense stocks performing particularly well. From 17 January 2017 to the time this article is typed, the stock of Boeing has doubled in price; the shares of Raytheon rose 35 percent, Lockheed Martin whooped 30 percent and General Dynamics 17 percent, respectively. The war economy of an empire is experiencing exciting times. Ties between Washington and Riyadh remain strong and unhinged.

Source: Website